Why the adventurer came home

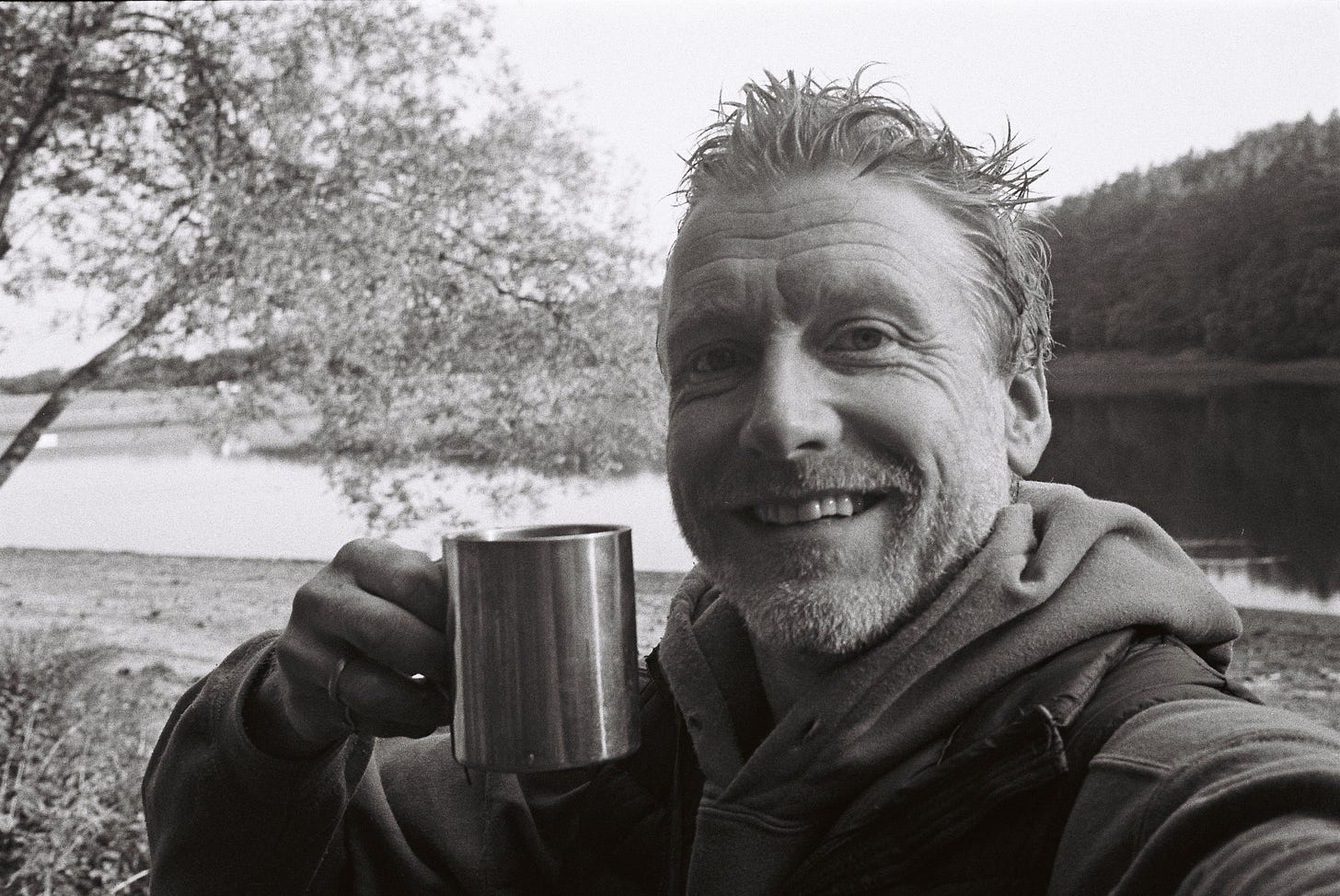

Alastair Humphreys: adventurer, author and speaker - Kent, England

(Rather hear the full conversation with Alastair? Here you go!)

“It’s the drug taker’s conundrum: how do you get your next hit? And the answer is you do something a bit bigger than the last one. And in the world of expeditions, that’s going to lead to you falling off a cliff and dying. Literally. Which I really didn’t want to do.”

Not settling for normal

Alastair Humphreys was having a “perfectly nice, happy, fun life” at university. But he’d started thinking, “Is this really it? Am I just going to graduate and get some job that I don’t really like because that’s what everyone else is doing, then I’ll do that for 50 years, and then I’ll join a golf club? Surely there must be a bit more I can do before I begin that normal life?”

As a youngster, he’d felt decidedly average, “I didn’t feel like I shone in any way in life,” yet was fascinated by stories of extraordinary human endeavours. “Throughout my time at university, I was inhaling expedition literature. It was very much reading those books that made me first think, ‘Wow, big adventures sound like a great thing to do.’” Sparking an interest which slowly morphed into “I wonder if I could do something like that…”

His motivation was, “To get to a point where I was looking forward to the rhythms and routines of normal life. And so I decided to pause that for a little while - by going off and doing something as stupid and crazy and hardcore and challenging as I could think of.”

So he decided to try and cycle around the world.

The arse-numbing reality of following your dreams

But this didn’t go exactly to plan. “Day one, I set off from my mum and dad’s house in Yorkshire.” But as soon as he was round the corner, “I burst into tears. I was thinking ‘This is the worst decision of my life. This is awful. I’ve split up with my lovely girlfriend to go and do this. All my friends are going off to do jobs and have fun, and I’ve condemned myself to this thing which is way out of my comfort zone. And it’s really scary. And my bum hurts’.”

Motivated by the fear he’d be “mocked forever” if he gave up this early on, he “limped down through England” with the sole aim of getting as far as France before giving up. But extrinsic motivation can be pretty persuasive, so he kept on going. “For about a year, I was very much motivated by what other people would think. And gradually … I started to care less about what other people think, and then the motivation started to become more intrinsic.” This internal drive led to him spending four years on his bike - crossing 60 countries, 5 continents, and cycling 46,000 miles.

Getting out of your head

Mastering the physical challenge was one thing, but “I hadn’t given any thought to the mental aspect of a long journey – how do you cope being on your own for so long?” As Alastair says, “Anyone can learn to ride a long way. It’s the mental side of things that are much more significant.”

He was exhausted by the “crazy emotional rollercoaster” of constant ups and downs. “You’re off in some amazing-sounding country, but you’re still just riding your bike every day, eating noodles, sleeping in a tent - the boredom, the repetition is all mixed in with the wonder, the glory, the fun and the excitement.”

Enduring these emotional extremes was test of resilience, something which Alastair still doesn’t think he’s overcome. “The highs were really wildly high, and the lows were really low - and there was no one to pick me up or moderate those things.”

But he reasoned, “I’ll get all this out of my system, then I’ll come home and be perfectly happy and normal, like all of my friends seem to be.”

A brutal comedown

Arriving back was a huge anti-climax, bringing a startling realisation, “Wow, I finished this massive thing, I’m still in my 20s, and the next 60 years are probably going to be a bit boring.”

Obviously, the only solution was to up the stakes. Again. And again. And again.

Over the next few years, Alastair proved he was anything but average. He ran 150 miles through the Sahara, walked across India, and crossed Iceland by foot and inflatable packraft. And while this was exciting, challenging and fun, he was “quite aware that just chasing more and more big adventures isn’t the solution to everything in life.” Reflecting on that time, he says, “I look back on it now as being a very selfish period. It was brilliant on a personal level, but it didn’t really add a jot to the universe.”

From macro to micro

Until now, Alastair had been enjoying writing about his adventures in the style of the books he’d read at university. In his words, “middle-class white man showing off about how cool he is.”

But was this what his audience wanted? While most people like the idea of adventuring, they often don’t have the freedom – or finances – to take six months off work to cycle across a continent or row across an ocean. So, he wondered, “Do we do nothing – or do we see what little things we can squeeze in around the margins?”

And that’s how he came up with microadventures: small and achievable ways of having adventures much closer to home. They’re something anyone can do: from pitching a tent in the woods overnight (and, if you’re brave, going straight into the office the next morning) to sleeping under the stars in your own back garden, being a tourist in your own city, or even simply taking a new route to work. It’s about seeing where you live in a new light. As Alastair says, “Adventure is only a state of mind.”

The movement took off – but not without a touch of irony. Whereas Alastair had been having big adventure after big adventure without much official recognition, “Once I started doing things like sleeping on little hills around London … suddenly I get the National Geographic nomination for Adventurer of the Year!”

The power of paying attention

Alastair’s purpose was evolving. “I used to go off, zooming across distant continents, and gradually I’ve got into exploring closer and closer to home”. And in doing so, he’s realised the value of slowing down: you find yourself paying more attention to what really matters.

“I recently spent a whole year exploring my local map.” Every week, he’d tackle a different spot near his home, at random. “My plan was to explore one grid square - one kilometre square - in complete detail.”

And doing this profoundly impacted him. “It’s not always beautiful nature … there’s a lot of litter, lots of blights on the landscape – even if you’re in the countryside. Once you start to pay attention, you start to realise that the so-called lovely green fields are actually wildlife deserts. The whole landscape, in many ways, is pretty trashed.” And now he feels, “a connection, a caring and a responsibility” to change things.

But why don’t more of us feel this way? As he points out, “You don’t chuck litter in your own back garden because you care about it. You feel a sense of stewardship: ‘This is my place, I’m going to look after it.’ So why don’t we feel that way when we’re out in the landscape?” We’ve become increasingly disconnected from the natural world. But that’s not the only problem, “There’s also the bigger question of why do we produce 20 billion plastic bottles every single day? This is a nuts society we’re living in.”

Slowing down to speed up change

To highlight these important issues, Alastair’s most recent pivot combines adventure with purpose. You can subscribe to his newsletter here.

“My purpose right now is to get more people to spend more time paying attention in nature.” He recommends spending at least 15 minutes a day somewhere close to home, and “really engaging with the outdoors”. Find a nearby park, field, riverside, wood - wherever you can get to - and then unplug your headphones, put your phone out of sight, and take time to notice - really notice - your surroundings.

He wants people to do this because it feels good - mentally and physically. But he’s hoping it’ll have a knock-on effect too: once you start noticing how bad things have got, “you’ll become inspired and motivated to take action and help fix it all!”

“A lot of really positive emotions [can] come out of the frustration and the anger and the fear and the sadness about the wrecked world. Once you start to do something, even something small, about it - like pick up some litter and encourage other people to get involved - that feels really positive,” he says. “You get this sense of achievement, a sense of accomplishment, that you’re actually doing something good.” And as he says, “If everyone fixes their own little spot - we’ve solved the world!”

Why saving the world has to feel good

While improving the state of the planet might be the end goal, Alastair’s adamant that any changes we make at an individual level should be enjoyable. He suggests finding ways to make your own life better that also make the world a little bit better too. “I think if you feel you need to start eating gruel, walking around in sacking, and generally having a miserable life, then no one’s going to carry that on for very long,” he laughs.

So how does Alastair avoid the martyrdom trap while still making a difference? He keeps a ‘not-to-do’ list on his wall to remind himself of what’s important, “A list of things I very specifically want to stop doing in my life.” This helps him focus his efforts on the things that matter the most, and which he enjoys the most too.

So, has he found his purpose? “I very much hope that what I strongly believe is my important purpose today isn’t the same as it is five or 10 years from now.” It’s clear he wants to continue learning and growing, “I hope in 10 or 20 years’ time, I look back and see myself now as a not very wise, naive person - and that I’m much wiser in the future!”

“I suppose my dream scenario would be that I finally write a book that makes a bunch of money, [so] I can buy some land and rewild it - and go surfing in the mornings! And then, through that rewilding process, encourage other people to make [better] choices and changes about nature and the environment.”

And would that be a legacy he’d like to leave the world? “Oh, that would be magnificent! I’d settle for that. Absolutely.”

Until then, he’ll continue exploring his local area, clearing up litter, and convincing people to spend 15 minutes under a tree - as it might just change how they see the world. Because sometimes the most meaningful adventures are the ones that happen closest to home.

To find out more or get in touch with Alastair, visit alastairhumphreys.com, search for him on socials at @al_humphreys or find him on Substack at Alastair Humphreys.

Uncut and unfiltered: the full conversation

This hour-long chat covers everything in the article - and much more. Discover how Alastair uses humour to embrace negative feedback, learn about his newfound love of old-school film photography, and find out why he’s got half a naked man in his shed.

(Full disclosure: this was my first attempt at hosting a podcast. It’s not going to win any awards, the sound’s a bit tinny, and I’ve kept it audio-only as I froze in front of the camera more than once! However, Alastair was (unsurprisingly) both inspiring and eloquent, so it’s worth a listen.)

So many inspiring ideas here that are so easy to emulate even for those of us without the stamina to ride off into the sunset - micro adventures, incremental achievements, the ‘what not to do’ list and more! Thank you for sharing!

A wonderful conversation - and I've just created and started a not-to-do-list a fab tool to more purposeful - thank you 🙏